Inside the Museum

Black Hawk

Black Hawk

As you enter the Visitors Center, you are surrounded by artifacts and Native paintings from local, as well as nationally renown, artists.

Black Hawk

Black Hawk

Black Hawk

(1767 - 10/31/1838)

Black Hawk, born in 1767, was a Sauk Indian chief and was noted for his struggles against the westward movement of the white settlers in Illinois. He rallied the Sac and Fox tribal allies to stand on their rights and remain in Illinois when white men pushed to make the Indians leave the state and illegally seized the Fox lead mines at Dubuque, Iowa, west of the Mississippi.

The Sac and Fox at that time were aligning with the Potawatomi, Winnebago and Kickapoo tribes to declare war on the whites.

At a council, the Sac and Fox agreed to settle west of the Mississippi, but later the talk of an Indian war started when Black Hawk crossed the Canadian border to visit the British Fort Malden, located in Amherstburg, Ontario.

Rumors that Black Hawk was leading a war party caused a confrontation with whites, which he won. He realized he would have to fight, and for two years he conducted a skillful frontier guerrilla campaign until the white man’s army finally reduced his warriors to a handful. Dressed in a white deerskin, the tribe’s symbol of peace, he surrendered at Fort Crawford, Prairie du Chien, Wis., on Aug. 27, 1832.

Black Hawk and his two sons were kept imprisoned at Fort Monroe in Hampton, Va., until 1833, then joined their tribe on a reservation near Fort Des Moines in Iowa.

Black Hawk died on the reservation on Oct. 31, 1838. His body was placed in a small shelter in Indian fashion. Later his bones were removed to the Historical Society Building in Burlington, Iowa. They were lost in a fire which destroyed the structure.

Buffalo

Black Hawk

Chief Ahpeahtone

This sculpture of the mighty buffalo was a gift from the Chickasaw Nation. He stands on the raised platform in the center of the room.

Chief Ahpeahtone

Chief Ahpeahtone

Chief Ahpeahtone

(1855 - 8/30/1930)

The last federally-recognized chief of the Kiowa, Chief Ahpeahtone was born in 1855. He was the son of Kiowa leader Red Otter and related by blood to Little Otter and Red Cloud, the famous Sioux Chief. His father’s brother was Kiowa chief Lone Wolf. He had a distinguished personality and was highly respected for his decision-making and leadership qualities.

He established the Kiowa Indian Hospital at Lawton, Okla., when it was a much-needed necessity for the Kiowa. The Lawton hospital has developed into a great institution, and now is part of the Indian Public Health Service.

Through his chieftainship, he decided to use the democratic system of nominating and voting. He developed the system and organization of the tribal business committees to transact tribal business. He knew and foresaw that this would be the best way to govern and lead the Kiowa people.

Ahpeahtone fulfilled the role of chieftain by self-support. He and his family were land allottees (their land was one mile west and 1/2 mile south of Carnegie, OK). They practiced row crop farming, and raised cattle and horses. He was a firm believer in education for the Kiowa and would travel where he could learn the modern way of living.

He always felt he had enough income to take care of himself and his family’s needs. His statement was always, “Why should my Kiowa people have to pay me for my services? This is not the way of chieftainship. To be a leader of the Kiowa people, I should be the biggest giver!” This only gift he ever received from the tribe was a new 1927 Model T Ford, which cost $550.

Ahpeahtone was a firm church believer, but also worshiped with peyote in the Native American Church. He belonged to the Gourd Dance Clan and composed some of the songs. He participated and danced in all the tribal dances.

In the spring of 1890, the “Messiah Craze,” a prophesy of the destruction of the white man and a return to the old times and the buffalo, arose among the Plains Indians. Ahpeahtone was chosen to visit the Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota Territory, where he was given a cordial welcome by his Sioux kinfolk. He then went to Fort Washakie, WY, to meet with the northern Arapahoes where he thought he would find the Messiah. They sent him on to the Paiutes in Nevada, and he found the prophet Sitting Bull in the upper end of Mason Valley, NV.

He was admitted to the presence of the prophet and soon satisfied himself that he was a fraud. On his way home, Ahpeahtone sent a letter to his sister, Mrs. Laura Pedrick of Anadarko, OK, about what he had discovered. She read the letter to the tribe, but they were not fully satisfied and when Ahpeahtone reached home, a great council was called to meet in Anadarko.

All the tribes came. The Arapahoes, who were in the area teaching the new way, were asked to come to the council. They made their talk and Ahpeahtone arose, told of his anxiety to know the truth, about his trip and his feelings of the fraud. The so-called Messiah Craze was exploded and the excitement soon passed away.

Chief Ahpeahtone died Aug. 8, 1930. He is buried at Rainy Mountain Cemetery, located south of Mountain View, OK.

Opothle Yahola

Chief Ahpeahtone

Opothle Yahola

(1824 - 1863)

In 1824 the Creek Nation was divided over the question of Indian removal because the federal government had an agreement with the State of Georgia to remove from its boundaries all Indians and transport them to the set-aside lands in the present state of Oklahoma. The chief of the Lower Creek Towns, William McIntosh, was for the removal, while the head of the Upper Creek Towns, Big Warrior, was against the removal; so the federal commissioners could not get a treaty.

In February 1825, Washington sent more commissioners to make a new treaty. The new Creek leader of the Upper Towns was Opothle Yahola. He was a handsome man who wore a beautiful blue tunic, a dark cravat like a white man, and an embroidered hat topped with feathers. Opothle Yahola refused to sign a treaty.

In 1826, he led a huge delegation of Creek chiefs and warriors to Washington to protest the Indian Springs Treaty signed by Congress. A new treaty was signed by Opothle Yahola on Jan. 24, 1826 and ratified by Congress. It ceded all the Creek lands in Georgia to the U.S. In 1828, the first of the Lower Creeks, led by McIntosh, moved to the new territory, now called Oklahoma.

In 1832, another treaty was signed by the Creeks, including Opothle Yahola, to cede all tribal lands east of the Mississippi to the U.S. The Creek people were free to move to the new territory or stay where they were. Tribal chiefs reigned but promises were not kept by the government. In 1836, the chiefs and leaders who protested conditions were taken captive and shackled, and their people were captured and removed to the new territory.

A treaty was signed with the Creek Nation in 1861, on behalf of the Confederacy. Creek opposition was led by Opothle Yahola, who took more than 5,000 men, women and children on foot, horseback and wagon, and left the Creek country for Kansas in November 1861, seeking refuge within the Union Army lines.

The “Loyal Creeks” on their way north were overtaken by Confederate troops and three battles were fought in which Opothle Yahola’s warriors were defeated. The survivors finally arrived in Kansas, where many of them remained until 1865.

Opothle Yahola died in 1863 at the age of 65, and was buried in a woodland burial ground near Belmont, KS.

Sitting Bull

Chief Ahpeahtone

Opothle Yahola

(3/1831 - 12/15/1890)

Sitting Bull was born on the south bank of the Ree River, now called the Grand River, at a place named Many Caches, near the present town of Bullhead, S.D., in March 1831. He was born into the Hunkpapa Tribe of the Sioux Nation. During his youth, he joined with his tribe in raiing their traditional enemies, such as the Crow and Assiniboin for horses.

He won distinction by battling with the Indian Nations. He wanted the white man to leave him alone. He would not allow the white man to ruin his nation, destroy the buffalo industry or starve his people.

Sitting Bull and other Sioux leaders took their followers to the pristine valleys of the Powder and Yellowstone rivers where buffalo and other game were abundant. He continually warned his people that their survival as free Indians depended upon the buffalo. During this time, Red Cloud of the Oglala subtribe was the leader of the Tetons but Sitting Bull’s influence as a holy man was steadily growing.

After Red Cloud signed the Fort Laramie treaty of 1868 (this treaty established the Great Sioux Reservation) and agreed to live on the reservation, his influence waned. Sitting Bull’s disdain for treaties and reservation life attracted not only followers from the Sioux, but also from Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples. In 1873, he had an encounter with Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer while Custer was guarding surveyors in Montana Territory for the Pacific Railroad. They would meet again at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. While Sitting Bull was not one of the war leaders in that fight, before the battle he had a vision in which he many soldiers, “as thick as grasshoppers,” falling upside down into the Lakota camp. His followers believed that his magical powers had led to the victory. Sitting Bull survived the battle, but the army forced him to flee to Canada.

Sitting Bull was the last man of his people to lay down his gun in 1881. He was held prisoner for two years after his surrender at Ft. Randall in the South Dakota Territory. After two years in captivity, he was allowed to live on the Standing Rock Reservation. In 1885 he joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show for a season, where he met Annie Oakley. Sitting Bull have her the nickname, “Little Sure Shot”, which she used for the rest of her career.

In 1888, when the government wanted to pay the tribe 50 cents an acre to break up the great Sioux Nation into smaller areas, he held the tribe together and got $1.25 an acre from the government.

A Ghost Dance in 1890 was causing unrest. On Dec. 12, 1890 a military order came for Sitting Bull’s arrest because the military was afraid of his influence and power. He was arrested in his cabin in the middle of the night and killed on Dec. 15, 1890.

Throughout his life, Sitting Bull was known for being a religious man, unpretentious, of good humor, charming, and possessed of power. He was a good husband and father and used his influence and wealth to patch up domestic quarrels for his family. He wore two eagle feathers in his hair, one of them red in remembrance of his wounds during battles.

Sitting Bull was born on the south bank of the Ree River, now called the Grand River, at a place named Many Caches, near the present town of Bullhead, S.D., in March 1831. He was born into the Hunkpapa Tribe of the Sioux Nation.

Sitting Bull was a religious man, unpretentious, of good humor, charming, and possessed of power. He was a good husband and father, and used his influence and wealth to patch up domestic quarrels for his family. He wore two eagle feathers in his hair, one of them red in remembrance of his wounds during battles.

He won distinction by battling with the Indian Nations. He wanted the white man to leave him alone. He would not allow the white man to ruin his nation, destroy the buffalo industry or starve his people.

In July 1868, Sitting Bull sent Hunkpapa leaders Gall and Bull Owl to sign the Treaty of Laramie, which established the Great Sioux Reservation. The military posts were closed and white people were not allowed in the area. Little by little the whites and armies violated this treaty.

Sitting Bull was the last man of his people to lay down his gun in 1881. He was held prisoner for two years after his surrender.

In the summer of 1885 he joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and toured Canada.

In 1888, when the government wanted to pay the tribe 50 cents an acre to break up the great Sioux Nation into smaller areas, he held the tribe together and got $1.25 an acre from the government.

A Ghost Dance in 1890 was causing unrest. On Dec. 12, 1890 a military order came for Sitting Bull’s arrest because the military was afraid of his influence and power. He was arrested in his cabin in the middle of the night and killed on Dec. 15, 1890.

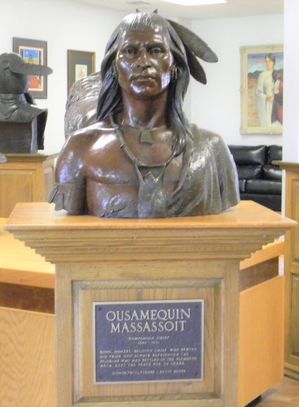

Ousamequin Massassoit

(1580 - 1661)

Ousamequin, meaning “yellow feather,” was the revered chief of the Wampanoag and called Massasoit, meaning leader. He was born about 1580 and resided primarily at Pokanoket, near present Bristol, RI. His dominion extended over Cape Cod, where the Pilgrims settled at Plymouth in 1620, and all of present Massachusetts and Rhode Island between Massachusetts and Narragansett bays, with vague boundaries extending westward.

Massasoit had become acquainted with whites before the Pilgrims arrived. Capt. John Smith of the Jamestown Colony likely visited with him when cruising the New England coast, and Capt. Thomas Dermer was in communication with him in 1619.

Samoset, a Pemaquid Indian and English-speaking friend of the Pilgrims, arranged a meeting with Massasoit and the leaders of the Plymouth Colony on March 22, 1621. Massasoit, his brother Quadequina, 60 warriors and Samoset appeared at the colony. Massasoit negotiated a treaty of peace and friendship with the colony, a treaty which was never broken.

In October 1621, Massasoit and 90 of his braves were invited to participate in a thanksgiving celebration at Plymouth. Massasoit and the colonists validated the peace treaty made earlier in the year and pledged their friendship in the spirit of thanksgiving, thus commencing a tradition which led to the official Thanksgiving holiday in the United States.

In little more than a year, Massasoit sent word to the Plymouth Colony that he was deathly ill, likely of typhoid fever. Immediately Edward Winslow, the chief Pilgrim negotiator of the peace treaty, and several other colonists went to visit him and administered treatment which aided his recovery.

In 1639 Massasoit sold the site of Duxbury, MA, to the English.

He died around 1661 at the age of 81.