Walking Tour

Betty Butts, Sculptress

Betty Butts, Sculptress

Betty Butts, Sculptress

As you approach the center, the sculpture on your left, beside that of Logan Billingsley, you will see a likeness of artist Betty Butts. Ms. Butts is honored for her continued interested in the Hall of Fame . Butts was a nationally-known artist, exhibiting her works across the US. On August 23, 1992, her fifth portrait in bronze, that of Chief Sitting Bull, was dedicated to the Hall of Fame.

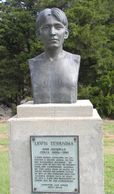

Simon Walkingstick Sr.

Betty Butts, Sculptress

Betty Butts, Sculptress

(5/8/1868 - 4/6/1938)

As you exit the museum building, take the path to the right. The first bust is that of Simon Ralph Walkingstick Sr., (Saw-one-oo-dov-larner-ste) who was born May 8, 1868 in the Goingsnake District, Indian Territory (I.T.) and was orphaned in his early life. He was Old Settler, East and West of the Mississippi and Western Settler Cherokee.

He attended and finished school at the Old Cherokee Male Seminary in Tahlequah, I.T. When he graduated, there were two other Cherokee men, George W. Bushyhead Sr., and W.W. Hastings, in his class. Walkingstick graduated from the University School of Law in Nashville, TN (formerly Cumberland, TN).

On May 23, 1889 he was admitted to practice law before the U.S. Supreme Court, Washington, D.C., and on May 31, 1909, he was admitted to practice before the Oklahoma State Supreme Court. He practiced law with former classmate Hastings in Tahlequah. He also worked with oil and gas leases throughout Oklahoma.

The Dawes Commission, established in the 1880s by the U.S. Congress, appointed Walkingstick to serve. The Commission, recorded all the people of the Indian tribes living in Indian Territory. He served until the Commission completed their work in 1907.

Walkingstick spoke all the languages of the Five Civilized Tribes: Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole.

He moved to Okmulgee, OK with his family in 1917 and re-established his law practice. He acted as an interpreter for non-Indian lawyers who were making oil and gas leases in 160-acre Indian allotments.

The old Walkingstick home, built in 1886, is located on Walkingstick Mountain on Walkingstick Road near Walkingstick Springs in Tahlequah, OK.

Walkingstick married the former Sallie Viola Osborn, with whom he had four children, Sally Ada, Simon Jr., Celeter (Leat) and Bruce. He married the former Rebecca Chandler, who was one-eighth Cherokee, in 1904. They had six children, Benjamin Taylor, Thomas (Tommie) Lowell, Galela Leona, Oliver Kenneth (O.K. Sr.), Howard Chandler, and Lorena May. He and Rebecca were co-founders of the First Methodist Church established in Tahlequah, OK.

Simon Walkingstick died April 6, 1938 in the Claremore, OK Indian Hospital. He is buried in the Okmulgee Cemetery.

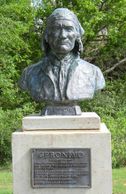

Osceola

Betty Butts, Sculptress

Will Rogers

(1804 - 1/30/1838)

Osceola, born as Billy Powell, became an influential leader of the Seminole in Florida. Billy was born in 1804 in the Creek village of Talisi, now known as Tallassee, AL, in current Elmore County. The inhabitants of the town were a mixture of Native American, English, Irish, Scottish and African-American. Powell apparently had ancestors in all of these groups. His mother was Polly Coppinger, a Creek woman, and his father was most likely William Powell, a Scottish trader.

Because the Creek had a matrilineal kinship system, Polly's children were all considered to be born into their mother's clan. They grew up as a traditional Creek family, gaining their status from their mother's people. When he was a child, they migrated to Florida with other Red Stick refugees after the defeat in 1814 in the Creek Wars. Upon entering adulthood, as part of the Seminole tradition, he was given the name Osceola. This is a combination of asi, the ceremonial black drink made from the youpon holly and Yahola meaning “shout” or “shouter”.

In 1821, the US acquired Florida from Spain. resulting in more European-American settlers moving in, encroaching on the Seminoles' territory. After early military skirmishes and the signing of the 1823 Treaty of Moultrie Creek, (which allowed the US seize the northern Seminole land), Osceola and his family moved with the Seminole into the unpopulated wilds of central and southern Florida.

In 1836, Osceola led a small group of warriors in the Seminole resistance when the United States tried to remove the tribe from their lands in Florida. He became an adviser to Micanopy, the principal chief of the Seminole from 1825 to 1849. Osceola led the Seminole resistance to removal until he was captured on October 21, 1837, by deception, under a flag of truce, when he went to a meeting spot near Fort Peyton for peace talks. He was imprisoned first at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, then transported to Fort Moultrie in Charleston, SC, where he died a few months later of causes reported as an internal infection or malaria. Osceola was well known and attracted visitors while in prison, including George Catlin, who painted perhaps the most well-known image of the Seminole leader.

Osceola was a major figure in securing the rights of Seminoles and during the colonial period—not through signing agreements and treaties with agents of the U.S. governments, as some tribal leaders had done, but through guerrilla warfare tactics that kept the U.S. military at bay for a long time. This slowed the removal of Seminoles and the taking of Seminole lands.

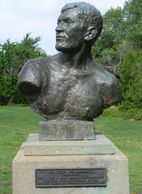

Will Rogers

Roberta Lawson

Will Rogers

(11/04/1879 - 08/15/1935)

Will Rogers was born Nov. 4, 1879 on his family’s Dog Iron Ranch near Oolagah, I.T. (Indian Territory). He was son of Clem V. Rogers, a successful businessman, and his wife, Mary (Schrimsher) Rogers. The youngest of his parents’ eight children, he was 9/32s Cherokee, and quipped that his ancestors didn’t come over on the Mayflower, but they “met the boat".

Will attended Kemper Military Academy in Booneville, MO, where a two-year stay completed his formal education after the 10th grade. Shown how to hold a lariat in his hands before he was five years old, he kept on playing with his rope through the years and learned to do fantastic tricks. He won the first prize in a roping contest in 1899 at Claremore, OK, the place he always called “home.”

He rode his favorite horse over the country looking for work as a cowboy. Next, he set out for “big ranching business” in Argentina. Soon penniless and starving, he left South America with a job on a cattle boat, shipping to South Africa.

Texas Jack’s Wild West Show, playing in Johannesburg, South Africa, offered him his first job in show business in 1902, and he was instantly a big hit with his rope act as “The Cherokee Kid.” His jokes about himself and others of the show as he twirled the rope with fast thinking and acting, got a big laugh from his audience. He traveled far and wide in vaudeville. He had the leading part in many stage shows and motion pictures. It was in his act with Ziegfield’s Follies during World War I he began slanting quips on celebrities in his audience.

Two books by Will Rogers were published. In 1922, he began writing a humorous column for the newspapers about leaders and happenings everywhere. Then came his radio programs which kept America laughing.

He was a philosopher of his time, sharpening the perspective on truth. He was a man of solid character, good and kind, saying, “I never met a man I didn’t like.”

There was deep sorrow throughout America when word came that Will had met his death in an airplane crash at Point Barrow, Alaska Territory on Aug. 15, 1935. He had started out for a tour of Russia. He was 55 years old.

He was buried in the beautiful garden of the Will Rogers Memorial at Claremore, OK on land Will purchased in 1911 to use as his retirement home.

Roberta Lawson

Roberta Lawson

Roberta Lawson

(10/31/1878 - 12/31/1940

Roberta Campbell Lawson, was a Lenape-Scots-Irish activist, community organizer, and musician. She was born at Alluwe, I.T. (Indian Territory), the daughter of J.E. and Emeline Journeycake Campbell. She was the granddaughter of the Rev. Charles Journeycake, the last tribal chief of the Delaware.

Roberta learned from both sides of her family; she was tutored at home and later attended a seminary and Hardin College in Missouri. From her mother and maternal grandfather Charles, she learned Lenape chants and music, which later inspired her own compositions.

She married lawyer Eugene B. Lawson on Oct. 31, 1901 and they established a home in Nowata, OK. When the first women’s club was organized in Nowata in 1903, Roberta became its president, serving for five years. The Lawson family moved to Tulsa, OK, in 1908, where their beautiful home was a tradition in Oklahoma hospitality.

During World War I, she was the head of the Women's Division of the Oklahoma Council of Defense. She was president of the Oklahoma State Federation of Women's Clubs, which organized to support community welfare and educational goals, from 1917 to 1919, and General Federation of Women's Clubs director from 1918 to 1922. She was a member of Tulsa’s Philbrook Art Center’s board of directors, and also served 18-years as a member of the board of regents for the Oklahoma College for Women in Chickasha, OK. She was a member of the board of directors of the Oklahoma Historical Society, and a trustee of the University of Tulsa at time of her death.

Always closely identified with the Delaware people, Lawson became distinguished within the tribe when she was elected national president of the National Federal of Women’s Clubs from 1935 to 1938, the first woman of American Indian descent to hold this office. During her three year term, she led its two million members to work toward goals of "uniform marriage and divorce laws, birth control, and civic service".

Roberta died from monocytic leukemia in her Tulsa home on Dec. 31, 1940. She was buried in Tulsa’s Memorial Park Cemetery.

José Maria

Roberta Lawson

Roberta Lawson

(1805 - 1862)

José Maria was chief of the Nadaco and principal chief of the associated bands of the Caddo, Nadaco and Ionies, frequently designated the “Caddo”.

Known as Iesh among his people, José Maria was born in 1805 near the Sabine River in East, TX where visiting Catholic missionaries christened him “José Maria”.

In 1835 he and other associated Caddo chiefs living in Louisiana signed a treaty providing all these tribes move away from U.S. territory. The chief led his people west to the Trinity and Brazos Rivers in Texas. He was wounded in 1841 during a skirmish between his group and a company of settlers led by George Bernard Erath. This is the only instance ever noted where he was involved in hostilities with whites. Accommodation made sense for the Nadacoans, by the mid-nineteenth century they numbered only 200 and lived under constant threat of attack from the Waco’s and the Tawakoni’s. As a result of this, José Maria turned to the white authorities for protection. Between 1843 and 1846 he signed a series of treaties surrendering sovereignty in return for protection and trade goods.

During these councils, he was spokesman not only for the Nadaco’s, but other Caddoan groups as well. In spite of his high standing among government officials, as well as his efforts to encourage a path of peace and the adoption of some aspects of white culture – José Maria was unable to prevent further expansion by frontier whites onto the land reserved for his people under the various treaties.

In 1848 he was concerned his people were in danger of being driven from their farms. This fear was heightened when, in the following year tribal lands were surveyed. The resulting situation was so unstable that in 1854, the Texas legislature voted to establish reservations for the state’s remaining Indians, the Nadacos accepted the offer readily. This resulted in the Nadaco and associated bands being assigned a reservation on the Brazos River. They prospered under José Maria’s leadership.

However, attacks on the Indians caused alarm and the government moved the group north, beginning August 1, 1859 to the Washita River in Indian Territory. Upon arrival, a census was made of the 462 who had survived the removal. The site where the group first encamped is now the city of Anadarko, OK, so named for the peace and friendship promoted by Chief José Maria.

José Maria was known as a leader who favored a peaceful coexistence. For courage and honesty, he attained his place as chief of all the associated Caddo bands and became a firm and loyal friend to many whites.

José Maria died about 186

Pascal Poolaw

Mitchell Red Cloud, Jr.

Pascal Poolaw

(1/29/1922 - 11/07/1967)

A full-blood Kiowa from Anadarko, OK, Sgt. 1st Class Pascal Cletus Poolaw, who served during World War II, Korea and Vietnam, was killed in Vietnam in 1967. He was 45 years old.

A total of 42 awards and medals, including four Silver Stars, five Bronze Stars, one Air Medal and three Purple Hearts — one for each war in which he fought, makes Poolaw the most decorated Indian soldier in U.S. history.

Poolaw was born Jan. 29, 1922 and attended Riverside Indian School, He married classmate Irene Chalepah March 15, 1940 at Rainy Mountain. The couple had four sons, all of whom were in the Army and three of whom served in Vietnam.

Sgt. Poolaw joined the U.S. Army Aug. 27, 1942, and rose through the ranks to earn a battlefield commission as a second lieutenant, but later relinquished his commission.

While in service to his country, he was wounded in Germany in Sept. 1944 and in Korea on April 4, 1951. He earned a Purple Heart with Oak Leaf Cluster, a Bronze Star with Oak Leaf Cluster, and a Silver Star with two Oak Leaf Clusters. He was awarded the Silver Star on Sept. 8, 1944 when he was with the 8th Infantry in Belgium. His citation to the third Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster to the Bronze Star was awarded for his service in the Korean War during 1950-51. He received his Silver Star in Korea on April 4, 1951.

Serving in a long line of military men, Poolaw served in World War II during the time his farther, Ralph Poolaw Sr., and his two brothers were also serving. His grandfather, “Kiowa George”

Poolaw, served as a member of the famed all-Indian Cavalry Troop L at Fort Sill at Lawton, OK, from 1893-95.

Poolaw served a year at Fort Sill before volunteering for duty in Vietnam. He had just completed his 25th year of service when he was killed by a rocket-propelled grenade on Nov. 7, 1967 He died while rescuing his wounded men who were under fire. His unit, Company C, 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry, was part of a search and destroy mission near the village of Loc Ninh, Binh Long Province, South Vietnam.

In 1968, Mrs. Poolaw received four medals awarded to her husband posthumously for service in Vietnam. Besides the Silver Star, she received the Bronze Star Medal, Air Medal and Purple Heart, given for wounds received Nov. 7, 1967.

1st Sgt. Poolaw is buried at the Fort Sill Post Cemetery, Fort Sill, OK.

John Ross

Mitchell Red Cloud, Jr.

Pascal Poolaw

(10/3/1790 - 8/1/1866)

John Ross, also known as Koo-wi-s-gu-wi (Mysterious Little White Bird), was the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1828–1866, serving longer in this position than any other person. Described as the Moses of his people, Ross influenced the Indian nation through such tumultuous events as the relocation to Indian Territory and the American Civil War.

He was born Oct. 3, 1790 in Turkeytown, AL., near Lookout Mountain, to Mollie McDonald, who was Scottish and one-fourth Cherokee, and Daniel Ross, a Scots immigrant trader who had settled among the Cherokee at the end of the American Revolution. As a result of his background, young John was bilingual and bi-cultural. After his schooling ended, he was appointed Indian agent in 1811. He served during the War of 1812 as an adjutant of a Cherokee regiment commanded by Andrew Jackson. Upon conclusion of the Red Stick War, John demonstrated his business acumen by starting a successful tobacco farm in Tennessee.

Ross was married in 1815 to a full-blood Cherokee woman name Quatie.

In 1817 Ross became a member of the Cherokee Nation, serving as its as president from 1819 to 1826. During his tenure, he helped draft the Cherokee Constitution of 1827. In 1829 he was elected principal chief of the eastern Cherokees and served until 1839, when he was chosen as chief of the United Cherokee Nation, an office he held until his death.

He vigorously resisted the efforts of the U.S. government to force the Cherokee to be removed to Indian Territory. Even the traditionalists of the tribe realized that John had the skills necessary to contest demands that the Cherokee cede their land and move beyond the Mississippi River.

Ross' first action upon being elected National Council president in 1818, was to reject an offer of $200,000 from the US Indian agency for the Cherokee to voluntarily relocate. Over the next several years, Ross made more trips to Washington. In 1824, he boldly petitioned Congress for reparations for Cherokee grievances. This was the first time a tribe had ever shown the audacity to do such a thing. Through his actions, Ross built political support in the capital for the Cherokee cause. All his efforts failed, however, and in 1838 and 1839 he led his people to their new home. The removal journey became known as the Trail of Tears. John’s wife, Quatie died in Arkansas on the way to Indian Territory.

John was instrumental in drafting the Constitution of 1839, uniting the eastern and western Cherokees under one government.

In 1844, John married a second time to a Delaware Quaker woman, Mary Brian Stapler,

When U.S. forces invaded Indian Territory in 1862, Ross went to Philadelphia where he made his home. He spent time in Washington, D.C., on behalf of the Cherokee Nation and it was there he died on Aug. 1, 1866 while assisting in making the Cherokee Treaty of 1866. Resolutions were passed for bringing his body from Washington at the expense of the Cherokee Nation for suitable funeral rites and burial in order “that his remains should rest among those he had so long served.” He was buried in Park Hill, OK.

Mitchell Red Cloud, Jr.

Mitchell Red Cloud, Jr.

Mitchell Red Cloud, Jr.

(7/2/1925 - 11/5/1950)

Mitchell Red Cloud Jr. was born July 2, 1925 near Hatfield, WI, to Mitchell Red Cloud Sr. and Lillian Winneshiek. He attended the Neillsville Indian School and the Komensky and Clay Country schools before entering Black River Falls High School.

In August 1941, Red Cloud received permission from his father to leave school at age 16 and enlisted in the Marine Corps. After basic training, he was assigned to the 1st Marine Division in the Pacific Theatre, where he served with the famed Carlson’s Raiders.

While engaging the enemy on Guadalcanal, Red Cloud contracted malaria and incurred a severe weight loss. By January 1943, he had lost 75 pounds and weighed only 115 pounds. He was evacuated to the U.S. for medical treatment. During his recuperation, he was offered a medical discharge, which he refused.

In December 1941, Mitchell returned to the Pacific and saw action on Okinawa and the Ryukyu Islands. He returned to the U.S. in October 1945 and was honorably discharged in December of that year.

Red Cloud joined the U.S. Army in 1948 and was sent to Korea in 1950. It was on Nov. 5, 1950, on a hillside outside Chonghyon, Korea, that he recreated the heroism of countless American Indians of days past and shed his blood so that others could live.

Mitchell was standing watch on a ridge in front of the command post and detected the approach of Chinese Communist forces. Without regard for his own safety, he gave the alarm as the enemy charged from a brush-covered area less than 30 yards from him. Springing up, Red Cloud delivered devastating point-blank automatic rifle fire into the advancing enemy. His accurate and intense fire checked the initial assault and gained time for the company to consolidate its defenses.

Although severely wounded by enemy fire, Red Cloud pulled himself to his feet, wrapped his arm around a tree and continued his deadly fire until he was fatally wounded. He was 26 years old.

For his courage, dedication and self-sacrifice, Red Cloud was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, which was presented to his mother by Gen. Omar N. Bradley. In 1955, his remains were returned from the U.N. cemetery in Korea for burial in Wisconsin.

Stand Watie

Muriel Wright

Mitchell Red Cloud, Jr.

(12/12/1806 - 9/9/1871)

According to the many biographers of this famous Cherokee Indian, Stand Watie was “one of the most picturesque and interesting figures in the history of the Civil War in Oklahoma.”

He was born Dec. 12, 1806 at Oothcaloga in the Cherokee Nation, near present day Rome, GA. His father, Uwatie, who went by his Christian name of David Uwatie, was full-blood Cherokee, and his mother, Susanna Reese, was of Cherokee and European descent.

He was a determined lad, who always made a firm stand and followed through with any task. Consequently, his name, De-ga-ta-ga, or “he stands” in the Cherokee language, was most appropriate during his younger years, and also when he became a capable leader of his devoted followers. He was also known as Isaac S. Watie.

He attended a Moravian mission school, near the Tennessee/Georgia line, where he received a good education. He soon became a man of prominence among his people, owning land, a beautiful home and many slaves.

He was one of the signers of the Treaty of 1835 by which the Eastern Cherokee agreed to sell their lands and remove to Oklahoma.

Watie was the distinguished leader and officer of the Southern Cherokee, the only Indian officer who attained the rank of brigadier general in the Confederate Army.

He was the last Confederate leader to surrender, and will always remain a tsa-la-gi, “brave man,” in the minds of Southern Cherokee descendants and reviewers of history.

He was elected principal chief of the Cherokee in 1862 after John Ross fled the Cherokee Nation for Washington, D.C.. Ross’ supporters refused to recognize Watie’s election and open warfare broke out between the “Union” and “Southern” Cherokees. After the Civil War ended, both factions sent delegations to Washington, where it was determined Ross the rightful chief. Watie served as a member of the Southern Cherokee delegation during the negotiation of the Cherokee Reconstruction Treaty of 1866.

After the Civil War, he remained in exile in the Choctaw Nation until 1867. He then returned to rebuild his home on Honey Creek, where he died on Sept. 9, 1871. He was buried in the old Ridge Cemetery, now called Polson’s Cemetery, in Delaware County, OK.

Pushmataha

Muriel Wright

Muriel Wright

(1764 - 12/24/1824)

Pushmataha means “the sapling is ready or finished.” He was a noted Choctaw Indian born on the east bank of Noxubee Creek in Noxubee County, MS, in 1764.

Before he was 20 years old, he had distinguished himself in an expedition against the Osage by the taking of five scalps. This incident earned him the name “Eagle” and won him a chieftaincy. Later he became mingo (hereditary chief) of the Six Towns District of the Choctaw and exercised much influence in promoting friendly relations with the whites.

Pushmataha fought in the War of 1812, serving under Gen. Andrew Jackson. While aiding the U.S. troops, he was so rigid in his discipline he soon succeeded in converting his warriors into efficient soldiers and became known as “The Indian General.”

In 1824 he went to Washington to negotiate another treaty on behalf of his tribe. Following this visit, he became ill with the croup and died Dec. 24, 1824 at age 60. He was buried with military honors. A procession of 2,000 persons, military and civilian, accompanied by President Jackson, followed his remains to Congressional Cemetery.

A shaft bearing the following inscription was erected over his grave: “Pushmataha, a Choctaw chief, lies here. This monument is erected by his brother chiefs, who were associated with him in a delegation from their nation, in the year 1824, to the general assembly of the United States".

Pushmataha was a warrior of great distinction. He was wise in council, eloquent to an extraordinary degree, and, on all occasions and under all circumstances, the white man’s friend.

General Jackson frequently expressed the opinion that Pushmataha was the greatest and bravest Indian he had ever known.

Muriel Wright

Muriel Wright

Muriel Wright

(3/31/1889 - 2/27/1975)

Muriel H. Wright, Oklahoma historian and author, was the granddaughter of Allen Wright, principal chief of the Choctaw from 1866 to 1870 and who gave the state of Oklahoma its name.

Muriel was born in Lehigh, Choctaw Nation, I.T. (Indian Territory), on March 31, 1889. She was one-fourth Choctaw and 11,153rd on the final roll of the Choctaw Nation of 1902. Her father, Dr. Eliphalet Nott Wright, was a physician and surgeon.

She attended Wheaton College in Norton, Mass., a school for women. In 1912, She completed a teacher education course at East Central State College at Ada, OK, although she didn’t receive a degree. After attending ECSC, she taught eighth grade at Wapanuka in Johnson County, OK. She also taught at Tishomingo, OK schools.

She attended Barnard College, the women’s unit of Columbia University in New York City from 1916-17. Due to World War I, she was unable to continue her studies and returned to Coal County, OK, to serve as principal of the rural Hardwood District School. During World War II, she taught Oklahoma history in the elementary and high schools in Dustin, OK.

She was active in Choctaw tribal affairs. She was employed by the Oklahoma Historical Society to research and write the history of the Five Civilized Tribes and other Oklahoma Indians.

Muriel’s notable book, A Guide to Oklahoma Indians, was released in 1951 by the University of Oklahoma Press. It is still used and sold widely.

She also contributed greatly to getting the Oklahoma Historical Markers on the state’s highways.

Muriel was a past president of The National Hall of Fame for Famous American Indians in Anadarko.

She died Feb. 27, 1975 in Oklahoma City, OK, after suffering a stroke.

Alice Brown Davis

Alice Brown Davis

Alice Brown Davis

(9/10/1852 - 6/21/1935)

Alice Brown Davis, chieftain of the Seminoles in Oklahoma (the only woman appointed to this position), was an outstanding leader in education and Christian culture among her people in the history of this country.

She was born Sept. 10, 1852 in the Cherokee town of Park Hill, I.T. (Indian Territory). Her parents were Dr. John Frippo Brown, a graduate of medicine in Scotland who was in U.S. government service when the Seminoles moved west from Florida, and Luby (Redbeard) Brown, member of the tribal clan of Seminole chiefs.

Alice’s first schooling was among the Cherokees. After the Civil War, when all the Seminoles settled in their own nation (present Seminole County, OK), she attended the Presbyterian Mission school near present Wewoka, OK. She served as a teacher before her marriage in 1874 to George R. Davis, a native of Indiana. Together the couple had 11 children.

Fluent in her native language, Mrs. Davis was well-known as an interpreter in the courts of Indian Territory, continuing this service in the state and federal courts throughout Oklahoma.

She taught in Mesukey School for Boys and Emahaka School for Girls where she was later superintendent. She became an authority in tribal affairs, made a journey to Mexico with respect to a Seminole land claim there, and visited Florida in the interest of Baptist missions among the Seminoles who had remained in the Everglades.

Always the devoted counselor and friend of her people, Mrs. Davis was their natural leader upon the death of her brother, John F. Brown, who was Principal Chief of the Seminole Nation for many years. She was appointed by President Harding to the position of Seminole chieftain in 1922. She served in this capacity until her death.

She made her home at Wewoka, OK where she died June 21, 1935 at age 82. She was buried in the family plot in Wewoka Cemetery.

Kicking Bird

Alice Brown Davis

Alice Brown Davis

(1835 - 5/4/1875)

Kicking Bird, Tene-Angop’te, a Kiowa peace chief was of Kiowa and Crow descent. While his exact birthplace is unknown, the Kiowa inhabited Western OK, the TX Panhandle and Southwestern KS at that time. He cut a fine figure with his handsome face and slim figure. He has been described as tall, sinewy, agile and very graceful. His good looks were a part of the charisma which made people want to follow him as their leader.

He was noted as a skillful military leader, and even those he fought and defeated praised him. When he rode off to battle, he was dressed in a white war bonnet and sat astride a spirited white horse. Though he was a great warrior who participated in and led many battles and raids during the 1860s and 1870s, he is mostly known as an advocate for peace and education in his tribe. He enjoyed close relationships with whites, most notably the Quaker teacher Thomas Battey and Indian Agent James M. Haworth. These relationships engendered animosity among many of the Kiowas, making him a controversial figure. He would become the most prominent peace chief of the Kiowas. Kicking Bird was diplomatically active and signed the Little Arkansas Treaty of 1865, the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867 and was instrumental in moving his people to reservations.

He was a famed statesman and his influence spanned an incredible range of people. He was well-known at Fort Larned, KS, where he monitored the Kiowa ration and annuity issuance.

He camped on Cache Creek, three miles south of Fort Still, OK; Two Hatchet Creek, two miles south of Fort Cobb, OK.; and near Murder Mountain, about three miles south of Fort Cobb. OK. There was a constant flow of people — military, Indian agents, traders and tribal members — around his lodge.

Kicking Bird worked hard to save his people by accomplishing the objectives of the Peace Policy. When other Kiowa leaders botched a peace council at Fort Cobb in 1872, Kicking Bird lobbied authorities for his tribe and because of his actions, a reversal was made on the ban of sale of firearms and ammunition to the Kiowa.

Kicking Bird was reportedly stricken with convulsions after breakfast on May 4, 1875. By 10 o’clock that same morning, he was dead at age 40. Supporters claimed he had been poisoned or cursed by his militant Kiowa enemies. He was buried in the Post Cemetery at Fort Sill, OK.

Tishomingo

Alice Brown Davis

Charles Curtis

(1737 - 1839)

Chief Tishomingo was born about 1737 in the old Chickasaw country, in present northeastern Mississippi. The Chickasaws had been aligned with the earliest English trading interests. They also had been involved in the Indian wars on the Mississippi colonial frontier.

Tall and of fine physique, Tishomingo was noted as a great warrior. He served with General Anthony Wayne against the Shawnee in the Northwest Territory, (1775–1783). For this he received a silver medal from President George Washington. He was known for leading warriors by example and was highly respected for his honesty, integrity and high moral standards. He went to battle with the Chickasaw in their last war with the Cherokees about 1769. He was again with his victorious tribesmen in a war with the Creeks from 1793-95. He served with distinction in the US military the War of 1812 and the Red Stick War (1813-14). During the War of 1812, he served under General Andrew Jackson.

For his bravery, his strong character and good sense, he was esteemed by his people. He was chosen as their tribal tishomingo, “ancient chief,” a title given a great leader who was to serve the hereditary chief (“minco” or “mingo”) under the old tribal form of government.

After his military service, Tishomingo retired for a time to be a farmer. About 1815, though Tishomingo was opposed to the innovation, the Chickasaw country was divided into four districts by the U.S. Indian agency, to facilitate the payment of the tribal annuities. Tishomingo became chief of one of these districts, and was a signer of these treaties with the United States.

He was the true leader of the Chickasaw, his word was the law representing their best interests. He signed the Treaty of Pontotoc in 1832, providing for the sale of the Chickasaw country in Mississippi for cash so when the Chickasaws moved west a few years later, they were the wealthiest of any of the Five Civilized Tribes.

In 1837, a final treaty forced Tishomingo and his family to move to the Indian Territory. On May 5, 1838, he died of smallpox on the Trail of Tears. He was buried near Little Rock, AR.

Charles Curtis

Charles Curtis

Charles Curtis

(1/25/1860 - 2/8/1936)

Charles Curtis was a member of the Kaw (for Kansa) Tribe and received his allotment of land in the Kaw Reservation in Oklahoma. Born Jan. 25, 1860 in Topeka, Kansas Territory, he spent the years of his childhood living with his maternal grandparents on the reservation, and in Topeka with his paternal grandparents.

Curtis was an attorney, and entered political life at age 32 winning multiple terms in his district, beginning in 1892 as a Republican to the US House of Representatives. He served as US Senator from 1907-1913 and 1915–1929 Curtis ran for Vice President on the ticket with Herbert Hoover, and was elected to that office, serving from 1929-1933. He was the first man of Indian descent to be elected to this high office.

In 1889, following the creation of the Dawes Commission, which resulted in the opening of the “Oklahoma Country” to white settlement, Curtis fathered the famous Curtis Act (approved June 28, 1898). The act resulted extending the Dawes act to the Five Civilized Tribes of Indian Territory. It ended their self-government and provided an allotment of communal land to individual households of tribal members. It limited the tribal courts and government. Further, any land not allotted to tribal members were to be considered surplus and sold to non-Indians.

Curtis was one of the most outstanding floor leaders in history, and gave more than 40 years of devoted service to his government and to the Indian people.

He married Annie Baird with whom he had three children, Permelia Jeannette, Henry King and Leona Virginia.

He died Feb. 8, 1936 in Washington, D.C., after suffering a heart attack at age 76. According to his wishes, his body was returned to Kansas and interred at the Topeka Cemetery.

Sacajawea

Charles Curtis

Sacajawea

(1788 - 1812)

Sacajawea, of the Shoshoni tribe which lived near the headwaters of the Missouri River in the mountains of western Montana, is famous in history for her services as guide and interpreter for the Lewis and Clark Expedition to the Pacific Ocean in 1805-06, which chartered the first pathway for the Americans in the Louisiana Purchase.

Born around 1788 in Idaho, her Shoshoni name, Sacajawea, which is best known in history, means “canoe launcher.” Another name given her by the Hidatsa tribe which had captured her as a child signifies “bird woman.”

In April 1805, Captains Lewis and Clark, with a guard of soldiers and other helpers, set out from near present-day Bismarck, ND, accompanied by the French Canadian trapper Charbonneau and his young wife, Sacajawea, who was carrying their infant son, Baptiste. She proved to be a dependable guide, and won the high regard and gratitude of all on the expedition for her bravery and resourcefulness in many difficult and dangerous places along the way.

Some time after the expedition to the Pacific, Sacajawea was awarded a special medal by the United States for her great service to the American people. Many art works have memorialized her as one of the greatest American Indians.

Historical documents suggest Sacajawea died in an epidemic of "putrid fever" late in in 1812, with her burial place unknown. Native American oral traditions related that she died April 9, 1884 in Wyoming and is buried near the Shoshoni Agency on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming.

In 2000, the United States Mint issued to Sacajawea dollar coin in her honor, depicting Sacajawea and her son. The face on the coin was modeled on a modern Shoshoni-Bannock woman since no contemporary image of Sacajawea exists.

Victorio

Charles Curtis

Sacajawea

(1820 - 10/13/1880)

Born in the early 1820's in the Black Range of New Mexico, Victorio was an Apache warrior known for being an intelligent and feared fighter. He proved his military cunning by leading small groups of warriors—often consisting of no more than 35 to 50 fighters—in triumphant resistance to American and Mexican troops.

Little is known about Victorio's early years, but it can be assumed that he spent some of his life learning to be a warrior. Learning to fight against the encroaching white people and other enemy tribes who all fought to keep the best land and supplies for their people was the way young Indian men proved their worthiness to be called “warrior”.

In the 1850’s Victorio engaged in raids in northern Mexico alongside the more famous Native Americans Nana and Geronimo. In 1862, he joined Chief Mangas Coloradas, serving under him in the successful war to drive the copper miners from Apache land. After Mangas died, Victorio become a tribal leader, as he was next in line to lead. Victorio was the last hereditary chief whose raiding bands roamed over the lands they inhabited without any obstacles to stand in their way. Their territory at the time included present-day southwest Texas, New Mexico, southern Arizona, and the northern Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua.

The U.S. Department of Interior was determined to put Victorio and his band on the San Carlos Agency in Arizona. Officials knew the land was not their homeland and the move would crowd Victorio’s people onto the San Carlos Reservation amidst their traditional enemies. Gen. Wilcox, commander of the War Department of Arizona, stated that Victorio was unjustly dealt with in the abrupt removal of his people from Ojo Caliente to San Carlos, and that such a removal, if not a breach of faith, was a harsh and cruel measure. Shortly after relocation, Victorio left the reservation with a group of approximately 40 warriors, leaving the remainder of his band at San Carlos. This small group would rather die than return to the San Carlos Agency and many were killed in New Mexico.

In the summer of 1879, Victorio crossed the border into Mexico and was hunted by both the Mexicans and Americans. In April 1880, Victorio was credited with leading the “Alma massacre,” a raid on U.S. settlers’ homes around Alma, N.M. On October 15, 1880, Mexican military soldier Colonel Joaqu'n Terrazas and Juan Mata Ortiz, the man who was his second in command, managed to encircle Victorio and his men. The Apaches fought bravely, but in the end Terrazas, Ortiz and their men slaughtered the band of Apaches, leaving only those few women and children who had been traveling with the band alive. Victorio himself, refusing to die an ignoble death, at the hands of his enemies, killed himself. The survivors were made prisoners and were taken to Chihuahua City where they were kept in custody for the next few years.

Tohausan

Quanah Parker

Quanah Parker

(1780 - 1866)

Called Little Bluff, Tohausan served with distinction as the head chief of the Kiowa for 33 years prior to his death in 1866. He negotiated peace with the Osage and returned the tribes precious taime (Sun Dance medicine bundle). He was a skilled diplomat and negotiated a lasting peace with the Cheyenne during the summer of 1840, as well as the first Kiowa treaty with the U.S. at Fort Gibson in 1837.

n 1834, artist George Catlin painted Tohausan’s portrait and it is preserved in the National Collection of Fine Arts in the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C.

Tohausan was a courageous warrior and belonged to the Real Dogs, an elite Kiowa military society whose membership was limited to the 10 bravest men in the tribe. He protested the proposal of the U.S. Commissioners in 1856 to restrict the lands of the Kiowa and Comanche to parts of western Texas and Indian Territory.

Tohausan was a recorder of Kiowa history by means of a pictorial calendar he maintained on a buffalo hide. He owned two painted tepees and because he was a graphic artist, it is assumed he had an active role in the painting of the shelters.

Tohausan had many descendants in the Anadarko, OK, area, including artists Charles Oheltoint, Silverhorn, Steven Mopope and Roland Whitehorse.

Some historians and writers have used the spelling “Do-hau-san” or “Do-hasan.” The descendants use the correct name of “To-hau-san.”

Artist Catlin’s description of Tohausan in 1834: “We found him to be a very gentlemanly and high-minded man, who treated the dragoons (Spanish soldiers) and officers with great kindness while in his country. His long hair was put up in several large clubs and ornamented with a great many silver brooches and extended down to his knees.”

Quanah Parker

Quanah Parker

Quanah Parker

(1852 - 2/23/1911)

Quanah Parker was born on the Great Plains in approximately 1852, son of Peta Noconi, chief of the Quahadi band of Comanche, and his white wife, Cynthia Ann Parker.

Quanah’s name is from the Comanche word kwania, meaning “fragrant.” His mother had been captured by the Comanche in an attack in Parker’s Fort, Texas in 1836, when she was 9 or 10 years old. She was recaptured by some Texas troops in a battle with the Quahadi in December 1860, and taken to her white relatives in Texas where she pined for her Indian family and died in 1870 of influenza.

Quanah took part in the Indian War on the Plains in the early 1870's as chief of the hostile Quahadi who finally surrendered in 1877 to Gen. R.M. McKenzie. The Quahadi settled with the Kiowa and Kiowa-Apache on their new reservation in what is now southwestern Oklahoma.

Quanah was living on the Kiowa, Comanche and Kiowa-Apache Reservation near Fort Sill, I.T. (Indian Territory), when he visited his mother’s family in Texas. After that meeting, he chose to use her family name of Parker.

Quanah was one of the most influential and prominent leaders of the confederated tribes on the Kiowa-Comanche Reservation for many years,. He encouraged them in stock raising and farming.

Quanah had five wives, and 25 children.

He died Feb. 23, 1911. His remains, and those of his mother, were taken from their original burial places in 1957 and re-interred in the Fort Sill Cemetery, where handsome stone monuments mark their graves.

Pontiac

Quanah Parker

Stumbling Bear

(approx 1720 - 4/20/1769)

Pontiac was born near Fort Defiance in the Maumee River country of present Ohio, around 1716-26. He became the chief and leader of the confederated tribes of the Ottawa, Potawatomi and Ojibwa, with great influence among all the tribes throughout the Mississippi Valley.

He was slightly over six feet tall, of heavy stature, with well-shaped features. He had many noble qualities of character — great power and virtue of mind, a strong intellect and commanding energy. He was sometimes crafty, subtle and high-tempered in his dealings with others, yet it was the humanitarianism about him which made him honored and revered for these traits by the Indian people.

He led the Indian forces on the side of the French in the battle which saw the British victory in the fall of Quebec. French trading posts were soon in the hands of the English and the Indians found themselves treated with contempt and neglect.

The tribes resented this and suffered from want and deprivation of articles they had in trade in the nearly 150 years of friendship with the French.

Pontiac rose as the Indian leader whose great genius as an organizer roused the tribes from the St. Lawrence River to the Gulf of Mexico in a war against the English, with the avowed purpose of saving this country for the Indian people.

He was forced to sign a treaty with the British in 1765. He still held himself with dignity, remembering the long friendship with the French.

In 1769, during an altercation that took place for unknown reasons, Pontiac killed Peoria Chief Black Dog. Perhaps in retaliation, and perhaps due to his increasingly amicable relationship with the British, Pontiac was killed by one of Black Dog’s nephews. The two had gone into a shop in Cahokia and as they left, Pontiac was clubbed by someone—as he fell, he was stabbed to death by the nephew. Pontiac was buried where the city of St. Louis, MO, now stands.

Stumbling Bear

Major General Clarence L. Tinker

Stumbling Bear

(1832 - 1903)

Kiowa Chief Stumbling Bear (Set-imkia, “bear that is pushing”) was born in 1832, the year of the Wolf Creek Sun Dance. A cousin of Kicking Bird, he was first noted during a Sun Dance held at Timber Mountain Creek. His brother had been killed recently by the Pawnee, and at the dance he sent the pipe around to recruit a revenge expedition. A large war party with several hundred warriors from seven tribes — Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, Comanche, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Osage and Crow — was organized.

The war party crossed the Arkansas River and met about 80 Sac and Fox and a few Potawatomi on Smoky HIll. The fight was disastrous. The Sac and Fox were armed with rifles and killed about 12 Kiowa and eight of their allies. But Stumbling Bear earned a chieftainship as a result of his leadership in this battle. He was 22.

In the winter of 1856-57, Stumbling Bear led a war party with Big Bow against the Navajos. He also led a war party with Satanta against the Utes in 1858-59. He headed battles in 1965 against Kit Carson in Texas, and made a name as a fierce warrior.

Stumbling Bear was present at the Medicine Lodge Council in 1867 at Medicine Lodge Creek in Kansas. This was the last treaty made between the U.S. government and the Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, Comanche, Cheyenne and Arapaho, except for a few agreements.

He was part of the peace faction because a doctor at one of the army posts saved the life of his small son who was gravely ill.

The government built Stumbling Bear a home in 1878 on the Kiowa Reservation in Indian Territory, one of the first Indian houses built, where he lived until his death in 1903.

Major General Clarence L. Tinker

Major General Clarence L. Tinker

Major General Clarence L. Tinker

(11/21/1887 - 6/6/1942)

Clarence L. Tinker, a native Oklahoman was born in the Osage Indian Nation, Nov. 21, 1887. He was the first American Indian in U.S. Army history to attain the rank of major general.

Tinker attended Wentworth Military Academy in Lexington, Mo., graduating in 1908. He entered the military as a third lieutenant in the Philippine Constabulary and served until March 1912, when he transferred to the infantry of the United States Army.

After assignments in the Hawaii Islands and along the Mexican border, Tinker began a 20-year career as a pilot. He graduated from the Air-Service Tactical School and the Army’s Command and General Staff School.

He moved to London in the summer of 1926 to be the assistant military attaché for aviation at the American Embassy. Shortly after arriving, Tinker earned the Soldier’s Medal for saving the life of a comrade after their plane crashed and burned.

He returned to the U.S. in 1927 and was assigned duties in Washington, D.C. During the 1930s he commanded various pursuit and bombardment units in California. He returned to Washington for duty as chief of the Aviation Division in the National Guard Bureau. Later he commanded the 27th Bombardment Group in Louisiana and Florida.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, he was appointed air forces commander of the Hawaiian department and ordered to reorganize the air defenses of the Central Pacific. In January 1942, Tinker received his second star and became the highest-ranking officer of Indian ancestry in the U.S. Army.

On June 6, 1942, while leading a bomber flight engaging the Japanese fleet near Wake Island, Tinker’s plane dived into the sea. He was the first American general lost in action in World War II; his body was never recovered. The Distinguished Service Medal was awarded posthumously to Tinker for his gallant action in personally leading this dangerous mission.

Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma City, Okla., was named for Major Gen.

Little Raven

Major General Clarence L. Tinker

Major General Clarence L. Tinker

(1810 - 1889)

Little Raven, also known as Hosa (young crow), chief of the Southern Arapaho, was born about 1810 in the Platte River region of present day Nebraska. In 1851 a vast tract of land was assigned to the Arapaho and their kindred tribe, the Cheyenne, by the U.S. government. Some members of the two tribes moved south towards Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas River where they became known as the Southern Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne.

Little Raven and the other chiefs signed a treaty with the federal government in 1861, reducing their lands to a smaller reservation in southeastern Colorado, with promises of implements, livestock and schools for the development of their people. Chief Little Raven was pleased with these prospects because the Arapaho had advocated agricultural living in the old traditional ways before they had secured horses (1750) and became buffalo hunters on the Plains.

At the Medicine Lodge Peace Council in 1867, Little Raven towered in intellect and oratory above the 5,000 Indians gathered there, his speech before the U.S. commissioners in the Council was a credit to any enlightened statesman. He was forthright in detailing the plight of the Indians, and in making a strong plea for their protection and better treatment by the government in the future.

He soon came with his people to the new Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation in western Oklahoma where he served as many years as a fine and kind leader. He opened and operated a good farm on the North Canadian River near where the U.S. Cantonment was later established in present Blaine County, OK. Chief Little Raven died there in 1889.

Satanta

Louis Tewanima

Louis Tewanima

(1820 - 10/11/1878)

Born in around 1820, Satanta (Set-t’ainte or “White Bear”) developed into one of the most effective orators among the Kiowa and one of the most well-known Indian chiefs in the Southwest.

He was the son of To-quodel-kaip-tau (Red Tipi) and spent his youth south of the Arkansas River following a general peace between the Kiowa and Comanche. His early manhood found him a fast friend of Satank and a well-known enough warrior to make a speech at the Medicine Lodge Council, held in October 1867 in Kansas. His rhetoric there won him the title of “Orator of the Plains.”

By 1871, Satanta was big news on the frontier, which was becoming more populated and tired of bloodshed. In May 1871, the Kiowa made a raid in the Red River region of Texas and the government ordered Satanta, Big Tree and Satank arrested for their part in it.

he Indian chiefs were apprehended at Fort Sill, OK, and sent to Ford Richardson in Jacksboro, TX, for trial. As the group left Fort Sill, Satank attempted to escape and was killed. Satanta and Big Tree continued to Fort Richardson where they were convicted and sent to Huntsville Prison in Texas.

In 1873 they were paroled and returned to Fort Sill and freedom.

By 1874, the Indians, Satanta among them, were once again on the warpath. They raided a government wagon train near the Washita River and turned themselves in to the Darlington Cheyenne Indian Agency. Satanta was immediately returned to prison at Huntsville.

Despondency seemed to set in and Satanta jumped to his death from prison window on Oct. 11, 1878. He was buried in the prison cemetery, but in 1965 his body was reburied at the Chief’s Knoll at Fort Sill. OK.

Louis Tewanima

Louis Tewanima

Louis Tewanima

(1888 - 1/18/1969)

Louis Tewanima, a Hopi tribal Antelope, was born in northern Arizona in 1888. Not much is known of his childhood, except he spent five years at Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, where he watched famed Sac and Fox athlete Jim Thorpe play football.

Carlisle coach Pop Warner told the 110-pound Tewanima he was too small for the track team, but Tewanima explained that all Hopis were fast runners. He proved he was a good runner and was not required to undergo team trials for the Olympics. Tewanima finished ninth in the 26-mile run in the 1908 Olympics in London. In 1912 at the Stockholm Olympics, he received a silver medal. His 1912 record held until Billy Mills broke it at the 1964 Tokyo Games.

In 1957 Tewanima was inducted into the Arizona Sports Hall of Fame and in

1974 a race was organized to honor the famed Hopi Olympian.

Tewanima lived most of his life in the Shungopavi village atop the Second Mesa at the Hopi Reservation in Arizona. He raised sheep and remembered the days of winning more than five track trophies for Carlisle School. In an interview, he confirmed he had run the 120-mile round trip to Winslow, Ariz., just to watch the trains when he was a youth. He also told of racing rabbits as a child.

At 80 years of age, Tewanima was still herding his sheep 20-30 miles a day. On Jan. 18, 1969, he attended a Kiva ceremonial on Second Mesa and, while going home in the dark, fell off a 70-foot cliff to his death.

Cochise

Louis Tewanima

Tecumseh

(abt. 1805 - 6/8/1874)

Cochise was born to Chiricahua Apache Chief Nachi in the spring of the early 1800's in the Dragoon Mountains of Arizona. The exact date of his birth is not recorded.

His Apache name, Cheis, meant “wood,” as he was lying on wood or his body was hard and firm as wood. When he first became a young man and had many feats of valor, he was given the name Cochise, which meant “hickory wood.”

During trading with the Mexican village of Concurpe, Nachi was traveling with his wife Alope, son Cochise and others in the tribe when the supposedly-friendly Mexicans turned on them with guns and knives. Nachi, Alope and Cochise escaped, but Nachi was gravely injured and died in his camp. Cochise became chief soon after.

Cochise was a great leader for his people. He saw in increasing number of covered wagons coming each day through their hereditary hunting grounds, and realized the traditional life of the Apache was ending. He tried to be peaceful and friendly with the whites, but when he was falsely accused by soldiers of kidnapping and some of his relatives were hanged, he transformed into their bitter foe.

He was described as “fully six feet tall, well-proportioned, with large, dark eyes; his face slightly painted with vermillion and his hair straight and black.”

He married Dos-teh-seh, the daughter of Mangus Colorado and they had two sons, Taza and Naiche.

When Cochise died June, 8, 1874, his sons directed their father’s burial in his stronghold in Arizona. He was dressed in his finest garments, his face decorated with war paint and eagle feathers on his head. He was mounted on his favorite horse and guided to a spot in the rocks of the stronghold to a deep cave. His horse and favorite dog were killed and dropped into the depths of the cave. His bows, arrows, lances and other weapons were thrown in also. Horses were ridden over the side after burial, so no one would know the exact spot he was buried.

Tecumseh

Hosteen Klah

Tecumseh

(1768 - 10/13/1813)

Tecumseh was born about 1768 in Ohio, the son of Shawnee chief Pucksinwa, who died at the Battle of Point Pleasant in 1774. Tecumseh is said to have served with the British as a young boy. He rose to prominence after the Revolution, not only as a warrior, but as a statesman. The settlers admired him because he did not allow torture of prisoners. He was known as a man who could be trusted with his word.

As a young Shawnee chief, he conceived the idea of a vast Indian confederacy. Most tribes claimed the right to dispose of their own hunting grounds, but Tecumseh claimed that land was held in common by all the tribes, and no one tribe could sell its particular tract. “Sell a country?” he thundered. “Why not sell the air, the clouds, the great sea ... Did not the Great Spirit make them all for the use of his children?” He made an effort to engage every border nation or remnant from the deep south of Florida to the far north of the upper Missouri River, his objective was to hold the Ohio River as a permanent Indian border.

Tecumseh thought the British were his friends and depended heavily on them to back him. As his confederacy drew closer to being a reality he had the town of Prophetstown, Ind., heavily stocked with provisions and stores. Former Indiana Territory governor and American general William Henry Harrison attacked near the settlement in what was called the Battle of Tippecanoe while Tecumseh was away, and Prophetstown was burned. All the provisions for the forthcoming confederacy were wiped out in that battle.

Tecumseh went to Canada to fight for the British and did very well. He became known as brilliant tactician and well-respected in battle.

During a retreat across Ontario from Fort Malden, Tecumseh persuaded the British commander to make a stand at the Thames River. Tecumseh was struck down during the height of the battle on Oct. 13, 1813.

Hosteen Klah

Hosteen Klah

Hosteen Klah

(10/1867 - 2/27/1937)

Hosteen Klah was a noted medicine man, wealthy stockman and unsurpassed weaver. His great-grandfather was the famed Navajo Chief Narbona, who at one time commanded all the Navajo warriors on the eastern slope of the Chuska Mountains of Arizona and New Mexico. His ancestors came to this land seven generations before his birth. Their clan name was Tzith-ah-ni, meaning “brow of the mountain.”

Klah was well-versed in the history of his people, handed down orally through the generations. He was born on Bear Mountain near Fort Wingate, NM, in October 1867. His mother was Ahson Tsosie and his father was Hoskay Nolyae. Four or five years after his birth, he was given the name Klah, meaning “left-handed,” because he used his left hand more readily than his right.

Klah’s uncle, medicine man Hail Chant, took Klah with him on many of his ceremonial and sick calls. He was probably one of the youngest Navajo boys to know a full ceremony. He could direct the sand paintings, sing the correct prayer chants and conduct the rites by the time he was 10. After his uncle’s death, Klah was the only chanter on the reservation who knew the complete Hail Ceremony.

When Klah was about 8 years old, it was discovered he was a hermaphrodite. The Navajos believed he was honored by the gods and possessed unusual mental capacity combining both male and female attributes.

On Feb. 27, 1937, Klah died from pneumonia at the Rehoboth Mission near Gallup, NM, and was buried, according to his wishes, in a white man’s cemetery in accordance with both the customs of the Indian and the white man’s ceremonies.

He did not live to participate in the dedication ceremony of the museum which was erected honoring his medicine lore and all the symbolic articles which pertained to his religion. His relatives agreed to have his casket disinterred and moved to a knoll beside the Wheelwright Museum in Santa Fe, NM.

T. C. Cannon

Hosteen Klah

Hosteen Klah

(9/27/1946 - 5/8/1978)

Pai-doung-a-day, “One Who Stands in the Sun,” was born Sept. 27, 1946 in Lawton, OK.

Pai-doung-a-day would be known to the art world as T.C. Cannon. His mother, Minnie Ahdunko Cannon, was of the Caddo Tribe and his father, artist Walter Cannon of Anadarko, OK, was a Kiowa tribal member. He attended public schools in Gracemont, OK, and in 1965 he attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, NM, where he studied with Fritz Scholder.

In 1967, Cannon served with the 101st Air Cavalry in Vietnam where he received the Bronze Star and two citations for meritorious achievement in ground operations against hostile forces. Upon return to the U.S. in 1968, he attended the College of Santa Fe and then Central State University in Edmond, OK, where he graduated in 1927 with a degree in art.

Cannon was a member of the famed Kiowa Black Leggins Warrior Society.

In 1972, the Smithsonian Institute honored him, along with Scholder, with a two-man show. He later made Santa Fe his permanent home.

In 1975, Cannon became artist-in-residence at Dartmouth College and it was here he established a collaboration with Japanese master woodcutter Maeda and master printer Uchikawa. The relationship resulted in the publication of what is known as the Memorial Woodcut Suite. His last completed masterpiece was Tosca — A Remembered Muse.

On May 8, 1978, T.C. Cannon was killed in a car accident near Santa Fe. He was buried at Memory Lane Cemetery in Anadarko, OK.

Geronimo

Jim Thorpe

Geronimo

(6/16/1829 - 2/17/1909)

Geronimo was a leader, but not chief, of the Chiricahua Apache. He gave June 16, 1829 as his birthdate, and Nodoyohn Canyon, AZ, as his birthplace.

He rose to leadership in a faction of braves by exhibiting extraordinary courage, determination and skill in successive raids of vengeance upon Mexicans, who killed his mother, wife and children in 1858.

Devastating Apache raids and massacres in Arizona and New Mexico brought action by the U.S. Army which placed Geronimo and other offenders on reservations. During the following decade, he led outlaw bands against American settlers. Geronimo surrendered in January 1884, only to take flight from the San Carlos reservation in May 1885, accompanied by 35 men, 8 boys, and 101 women. Lieutenant Colonel George F. Crook threw his best men into the campaign, and 10 months later, on March 27, 1886, Geronimo surrendered at Cañón de Los Embudos in Sonora. Near the border, however, fearing that they would be murdered once they crossed into U.S. territory, Geronimo and a small band bolted. As a result, Brigadier General Nelson A. Miles replaced Crook as commander on April 2.

During this campaign, no fewer than 5,000 troops and 500 Indian auxiliaries had been employed in the apprehension of an Apache band consisting of 35 men, 8 boys and 101 women who operated in two countries without bases of supply. Five months and 1,645 miles later, Geronimo was tracked to his camp in the Sonora mountains.

At a conference (Sept. 3, 1886) at Skeleton Canyon in Arizona, Brigadier General Miles induced Geronimo to surrender once again, promising him that, after an indefinite exile in Florida, he and his followers would be permitted to return to Arizona. The promise was not kept. Geronimo and his fellow prisoners were put at hard labour, and it was May 1887 before he saw his family again. He moved to Fort Sill, in Oklahoma Territory, in 1894, and at first attempted to “take the white man’s road.” He farmed and joined the Dutch Reformed Church, which expelled him because of his inability to resist gambling. He never saw Arizona again, but, by special permission of the War Department, he was allowed to sell photographs of himself and his handiwork at expositions. Before he died, he dictated to S.S. Barrett his autobiography, Geronimo: His Own Story.

While riding home in February 1909, he was thrown from his horse and laid in the cold all night before a friend found him. Geronimo died of pneumonia Feb. 17, 1909 and is buried at Fort Sill, OK.

Hiawatha

Jim Thorpe

Geronimo

(Dates unknown)

The first person known to bear the name was a noted reformer, statesman, legislator and magician, justly celebrated as one of the founders of the League of the Iroquois, the Confederation of Five Nations.

Tradition also makes him a prophet. He probably flourished about 1750, and was the disciple and active coadjutor of Dekanawida.

These two sought to bring about reforms to end of all strife, murder and war, and the promotion of universal peace and well-being.

Of these, one was the regulation to abolish the wasting evils of an intertribal blood-feud by fixing a more-or-less arbitrary price — 10 strings of wampum, a cubit in length — as the value of a human life. (It was decreed that the murderer or his kin must offer to pay the bereaved family not only for the dead person, but also for the life of the murderer, who, by his sinister act had forfeited his life to them, and that therefore 20 strings of wampum should be the legal tender to the bereaved family for the settlement of the homicide of a co-tribesman.)

By birth, Hiawatha was probably a Mohawk, but he began the work of reform among the Onondaga, where he encountered bitter opposition from one of their most crafty and remorseless tyrants, Wathatotarho.

Although the poet Longfellow chose the name Hiawatha for the hero of his Ojibway legend, historically Hiawatha was an Onondaga of the Iroquois federation. A famous counselor of peace, his efforts resulted in the League of Five Nations (later to become six) to which the Indian name “Iroquois” refers.

Known as “the official guardian of the council fire of the Iroquois,” Hiawatha represents the incarnation of human progress and civilization in all things, including the arts. As an Iroquois hero, he was a contradiction of the Indians’ reputation for cruelty and revenge.

Jim Thorpe

Jim Thorpe

Chief Joseph

(5/28/1888 - 3/28/1953)

Jim Thorpe (Wa-tho-buck, “Bright Path”), of the Sac and Fox Tribe (also part Potawatomi), is regarded in history as the world’s greatest athlete.

He was born May 28, 1888 near Prague, Indian Territory. He was the son of Hiran P. Thorpe, of Irish and Sac-Fox Indian descent, and Charlotte View, of Potowatomi and Kickapoo descent. He grew up with five siblings, although his twin brother, Charlie, died at the age of nine. Jim's athletic abilities showed at a very early age, when he learned to ride horses and swim at the age of three.

Thorpe first attended the Sac-Fox Indian Agency school near Tecumseh, OK, before being sent to the Haskell Indian School near Lawrence, KS, in 1898. In 1904 at age 15 entered the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania.

Jim became noted on Carlisle’s field of sports as both a star football player and all-around athlete. While playing football for Carlisle under coach Pop Warner he was chosen as halfback on Walter Camp’s All-America teams in 1911 and 1912. He was a marvel of speed, power, kicking and all-around ability. Also in 1912 he represented the US in the Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden. He won the decathlon and pentathlon by wide margins. However, when it was discovered in 1913 that Jim had played semi-professional baseball in 1911, his gold medals were taken from him and his Olympic records erased from the books.

From 1913-1919, Thorpe was an outfielder for National League Baseball teams in New York, Cincinnati and Boston. He moved to professional football in 1919 and was one of the early stars of the sport until he left the game in 1926.

Adjusting to life outside sports was difficult for Jim. But in his later years, he was still celebrated in magazine and newspaper articles as one of the greatest athletes of all time.

Jim died March 28, 1953 in Lomita, Calif., after suffering a third heart attack while eating dinner.

In 1955 the Jim Thorpe Trophy was awarded annually to the MVP in the NFL. In 1973 the Amateur Athletic Union restored his amateur status, and the International Olympic Committee finally recognized this in 1982. In 1983 his Olympic gold medals were restored to his family. Beginning in1986 the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame annually bestows the Jim Thorpe Award to the top defensive back in college football.

Jim is buried at Jim Thorpe, PA, which had been renamed in his honor upon his death in 1953.

Chief Joseph

Chief Joseph

Chief Joseph

(3/3/1840 - 9/21/1904)

Joseph, Hinmaton-yalakit, was an intrepid warrior and leader of the Nez Perce of southwestern Oregon. He was born March 3, 1840 in the Wallowa Valley of Oregon.

In 1871, as his father, Joseph the Elder, lay dying, he told young Joseph never to sell his country as others were doing. Young Joseph said, “I love this land more than all the rest of the world. A man who would not love his father’s grave is worse than a wild animal. I promise that I will never sell this country.” Young Joseph became chief upon his father’s death.

When Chief Joseph became leader, he followed the same path of peace his father had, but the close proximity of the whites led to killings on both sides. The whites wanted the Indians moved out of Oregon. Joseph spoke with the white leaders, saying he would not go to a reservation.

In the war following the cession of their tribal lands in the Treaty of 1883, Chief Joseph, leading his small band in a 1,000-mile retreat, displayed such generalship as to inspire one historian to describe it as “worthy to be remembered with that of Xenophon’s Ten Thousand.” Joseph was forced to surrender, and under military escort he and his band, reduced to 431, were taken to Indian Territory.

In 1885 the Nez Perce were permitted to return to their beloved Northwest, with half the tribe located at Lapwai and Joseph with the other half located in the Colville Reservation in Washington. He was allowed in 1899 and 1900 to return to the former lands near Wallowa in northeastern Oregon and stand with tears in his eyes at his father’s grave.

Chief Joseph died Sept. 21, 1904 on the Colville Reservation and is buried in Nespelem, WA.

Sequoyah

Chief Joseph

Black Beaver

(1764 - abt. 1843)

Sequoyah is famous in history as the inventor of the alphabet for his people, the Cherokee, a contribution in letters made by no other single individual in the history of mankind.

Born in the mountain country of present eastern Tennessee about 1764, Sequoyah had no formal education, knew no English and spoke only his native Cherokee tongue. Yet in 12 years, he completed at his home in Alabama his greatest work on the Cherokee alphabet, bringing his people the gift of the written word.

A skilled silversmith in his earlier years, his English name, “George Guess,” or “Gist” was the trademark of excellent workmanship.

He moved to Arkansas where he was a recognized leader of the Western Cherokees, and in 1828 signed the treaty that gave present northeastern Oklahoma to the Cherokee Nation. His log cabin home near Sallisaw, OK, in Sequoyah County, is enclosed in a stone building which stands as one of Oklahoma’s historic shrine.

Between 1843-1845, he died during a trip to Mexico while in search of a lost band of Cherokees. His burial place is unknown.

Black Beaver

Chief Joseph

Black Beaver

(1806 - 5/8/1880)

Black Beaver, Se-ket-Tu-Ma-Quah, renowned Delaware Indian scout and guide of many U.S. government exploring expeditions throughout the Southwest, made seven treks over different routes to the Pacific Coast. He was a guide with a military escort under the command of Capt. R.B. Macy who accompanied the famous wagon train of gold seekers to the California gold fields in 1849, charting the long-used “California Road” west from Fort Smith, AR.

Black Beaver was born 1806 at the site of Belleville, IL, and came southwest as a young man. His band of Delaware lived as neighbors to the Absentee Shawnee near the Oklahoma-Arkansas boundary. Black Beaver’s band lived in many places south of the Canadian River in Oklahoma before the Civil War.

He was interpreter to Col. Henry Dodge on the noted Leavenworth (or Dragoon) Expedition from Fort Gibson to the Wichita village on the Red River in 1834, for the first council between the U.S. and the Plains Indians of Oklahoma.

He and members of his band went to Kansas and served as scouts for the Union army during the Civil War.

After the war, Black Beaver and his friend Jesse Chisholm returned and converted part of the Native American path used by the Union Army into what became the Chisholm Trail. They collected and herded thousands of stray Texas longhorn cattle by the Trail to railheads in Kansas, from there the cattle were shipped East, where beef sold for ten times the price in the West.

Black Beaver resettled at Anadarko, where he built the first brick home in the area. He had 300 acres of fenced and cultivated land as well as cattle, hogs and horses. He became a preacher in the Baptist church, and was counted as a leader among the Indians of the Wichita Agency.

He had three, perhaps four, wives and four daughters.

Black Beaver died May 8, 1880 and was buried in a government plot near his old home place in Anadarko, OK. His remains were moved to the Chief’s Knoll at Fort Sill, OK, in 1975.

Pocahontas

Allen Wright

Allen Wright

(1595 - 3/21/1817)

Pocahontas, also called Matoaka (both names signifying “playful” or “amusing” in the Algonquian language), was born in 1595 near the James River in Virginia, the “dearest” daughter of Powhatan, chief of a confederation of Indian Tribes.

When she was 12 years old, she saved the life of Capt. John Smith of Jamestown. Her act of mercy made her important in the contest for power between Powhatan’s tribe and the Jamestown colonists.

In 1613, the colonists, fearing Indian war, abducted Pocahontas and held her hostage in Jamestown. She made friends with the women there, showing them how to prepare food found in this country, and helping nurse the sick. She was treated with kindness and became a Christian convert.

John Rolf, an “honest and discrete” young colonist, asked Gov. Thomas Dale for permission to marry Pocahontas in April 1614. They made their home near Henrico where Rolf, along with Indian aid, improved the growing of tobacco and learned how to cure the leaf for overseas shipping. He promoted the tobacco trade in England which soon flourished, thereby establishing the economic life of the Virginia colonists.

The Rolfs, with their little son Thomas, and a party of Indian relatives, visited England in 1616. Pocahontas, gracious and dignified, was entertained by royalty and everywhere acclaimed with honor. When the Rolfs were about to sail home to America, Pocahontas became ill and died March 21, 1817, at age 22. She was buried in the chancel of St. George’s Church at Gravesend, England.

Allen Wright

Allen Wright

Allen Wright

(1826 - 12/2/1855)

Allen Wright (Kilihote, “let’s go and kindle a fire”) was Principal Chief of the Choctaw Nation from 1866-1870. He was renamed Allen Wright upon attending school in 1834.

He was born in 1826 in Mississippi, and moved with his family in 1833-34 to the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory.

As minister of the Gospel, educator, translator and statesman, Wright was the great leader in the advancement of his people and the development of the state of Oklahoma.

One of the first Choctaw boys sent to an eastern college in 1848, he graduated from Union College in Schenectady, NY, in 1852 and from New York City’s Union Theological Seminary in 1855. He was the first Indian from Indian Territory awarded an M.A. degree.

He served his nation in many capacities and was a delegate in the making of the Choctaw-Chickasaw Treaty of 1866 in Washington, DC.

Wright suggested the name “Oklahoma” for the proposed organization of the Indian Territory.

He married Harriet Mitchell in 1857, and the couple had eight children. They were also the grandparents of historian Muriel H. Wright.

He died Dec. 2, 1855 and was buried in the cemetery at Old Boggy Depot, in present Atoka County, OK.